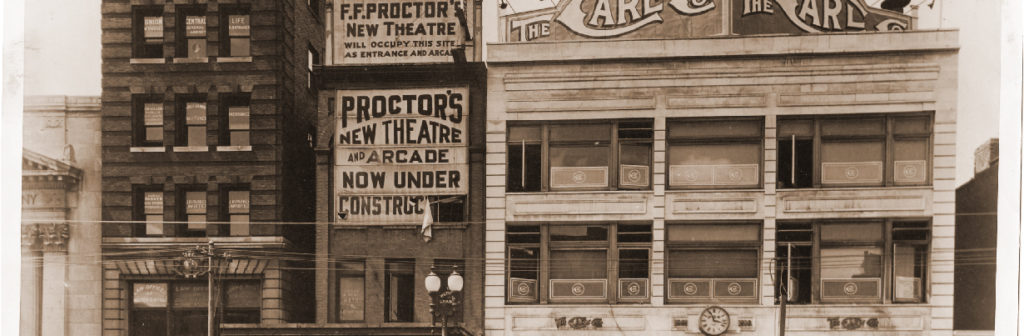

First Public Demonstration of TV

Fun fact. The first public demonstration of that newfangled idiot box, television, was held at Proctors, May 22, 1930.

What? TV at Proctors? Yes, it’s our fault. Sort of.

General Electric was already well ensconced in Schenectady by the time Proctors opened in late 1926. GE was also heavily invested in the concept of broadcasting, in addition to its other far-reaching technical pursuits.

The concept on that fateful May day was simple. A conductor, whose name, sadly, has been lost to history, stood in a house on the GE Realty Plot—a 90-acre neighborhood east of Union Avenue, boasting the first two fully electrical houses in America. An orchestra sat on onstage, a few miles away, at Proctors.

In between was the Swedish-born Ernst Alexanderson, the whiz-bang GE scientist who had already pioneered radio—playing fiddle himself in the first ever a.m. radio entertainment broadcast on Christmas Eve, 1906.

Ernst Alexanderson, GE scientist.

In Alexanderson’s fertile mind, the conductor, in front of a camera, would swing his baton, and the pit musicians, watching the maestro on a screen stretched across the Proctors stage, would play at his command.

Amazingly, it worked.

In these days of cell phones and on-demand viewing, we largely take television for granted, but imagine the surprise, the awe, of an audience in a darkened theatre, seeing a genuinely live broadcast.

If silent movies had disrupted vaudeville, if talkies had blown minds, what was to come from this new technology. We all know the answer to that, because we’ve lived through it.

Movies would move out of the cities, to the suburbs, largely taking the live audience with them. Then, as it grew and grew, TV kept the new suburbanites home more and more.

But for that—literally—shining moment in 1930, television was pure magic, and it happened first at Proctors.

In a wonderfully ironic bit of turnabout being fair play, the same concept that launched television still happens fairly frequently at Proctors, even now.

If you’ve ever sat in the orchestra section, forward of the balcony, you may have looked up and noticed a handful of flat television screens attached to the prow of the dress circle.

What are they doing there? Are the actors going to catch up on Westworld or Game of Thrones while they work?

Not exactly.

The actors watch the screen to view the conductor, who is facing a camera in the pit.

The singers need to know where they are in the music and the dancers need to find the downbeat. If they were to look to the pit they wouldn’t be looking at the audience, which is their job.

By occasionally glancing upward, they know right where they are, just as Alexanderson’s long-gone players did nearly 90 years ago.

Some things, it turns out, never change.